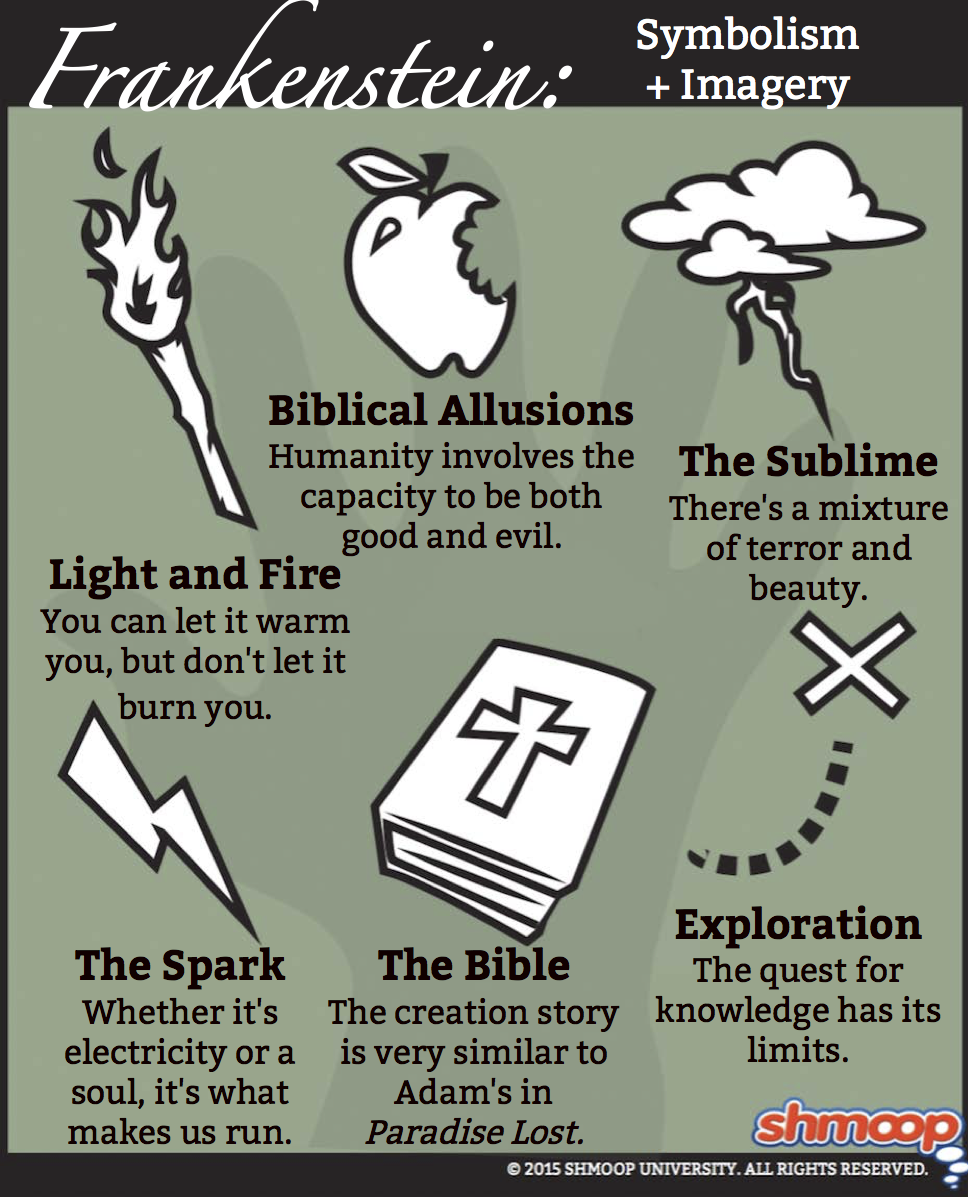

Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory

(Click the symbolism infographic to download.)

Mary Shelley may not have known about UV radiation and melanomas, but it doesn't take a scientist to know that a sunburn is bad news. You also don't need to know about endorphins and vitamin D to know that being in the sun feels good; that light feels safer than darkness; and that raw meat is (usually) super gross. In Frankenstein, light and fire represent the duality of progress and innovation: a fire might keep you warm, but you sure don't want to get too close.

Shelley establishes light as a symbol on the very first page, when Walton tells his sister that he's heading off to a "country of eternal light" where the "sun is forever visible" (Letter 1.2) and then keeps it up by having Frankenstein experience his insight as "a sudden light … so brilliant and wondrous" (4.3) But things go wrong quickly.

We get our first indication that light isn't all good when the monster's first sensation is of "light pressed upon [his] nerves" (11.1). His experience of light isn't awesome and science-y at all: it just allows people to see exactly how hideous he is. Like the fire that gives him warmth and then burns him (11.6), the light of science is good until you get too close—or pursue it too far.

It's no coincidence that Victor's interest in "real" science dates from the moment he sees lightening destroy a tree—and it's no coincidence that the monster burns the cottage to the ground when Agatha and Felix reject him.

Want to know more about fire in Frankenstein? Check out our discussion of Prometheus in "What's Up With the Title?"