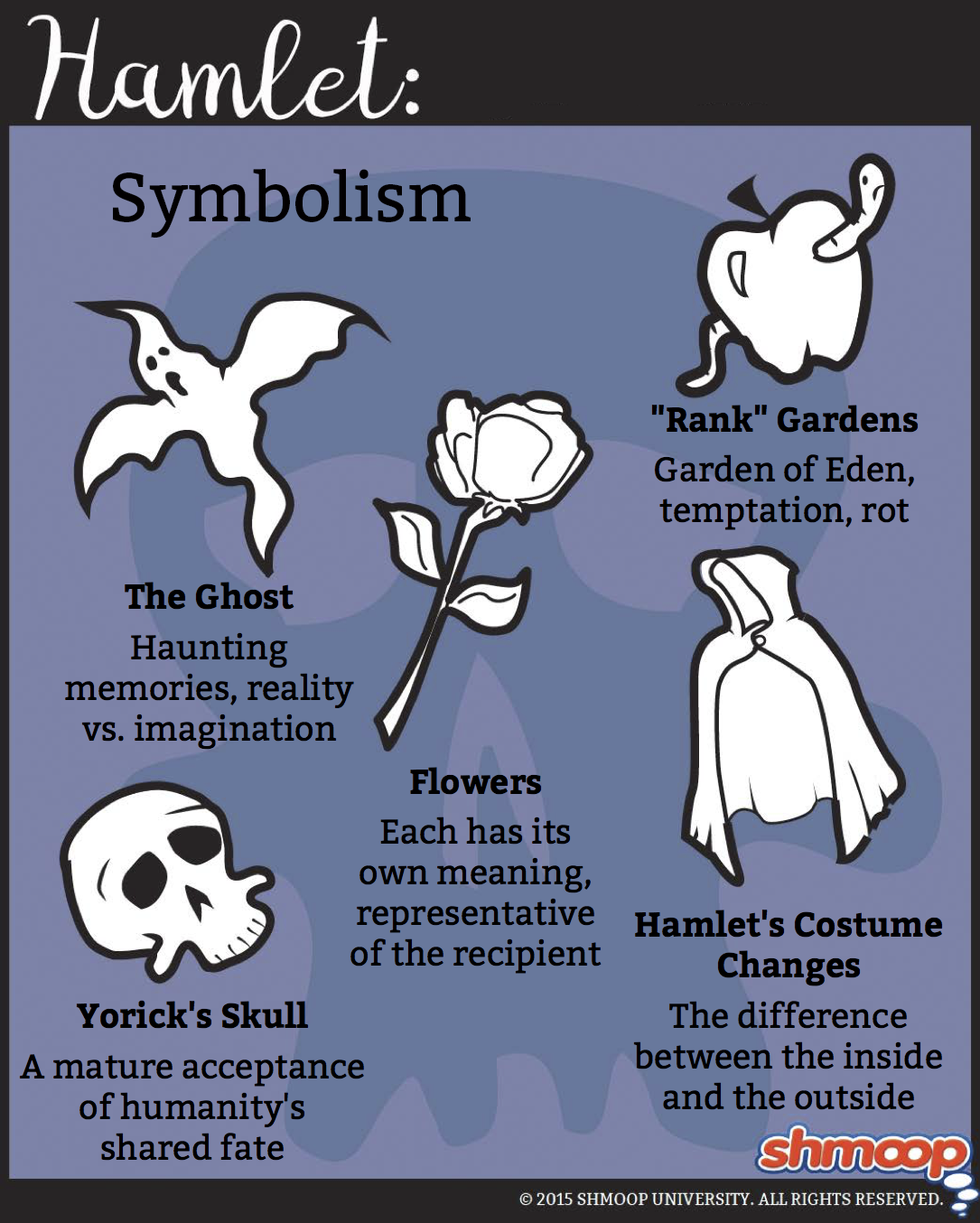

Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory

(Click the symbolism infographic to download.)

Hamlet's constant brooding about death and humanity comes to a (grotesque) head in the infamous graveyard scene, where Hamlet holds up the unearthed skull of Yorick, a court jester Hamlet knew and loved as a young boy. The skull itself is a physical reminder of the finality of death. After all of Hamlet's brooding and philosophical contemplation of mortality, Hamlet literally looks death directly in the face right here.

As you can probably guess, it's a turning point for Hamlet. He thinks about the commonness of death and the vanity of life. He not only remembers Yorick, a mere jester, but also considers what's become of the body that belonged to Alexander the Great. Both men, concludes Hamlet, meet the same end and "returneth into dust" (5.1.217). Morbid? Sure. But it also seems like a new, more mature acceptance of a common human fate. He may be contemplative, but he's not melodramatically contemplating suicide or anything.

Act Your Age

There's also a weird part in this scene where Hamlet all of sudden appears to be a lot older than we thought. When the play begins, Hamlet is a university student, which means he's pretty young. By the time Hamlet makes it to the graveyard in Act V, he's apparently thirty years old (much older than the average university student). The evidence? The First Clown says he's been a gravedigger in Elsinore since "the very day that young Hamlet was born" (5.1.152-153) and a few lines later he reveals that he's been a "sexton" in Denmark for "thirty years" (i.e. working at the church and graveyard) (5.1.167).

Sure, maybe Shakespeare just messed things up. It happens. But it wouldn't surprise us if Hamlet literally aged between Act I and Act V —perhaps it's a reflection of his new, more mature outlook on life and death.

Necropolis

One more thing: In this scene, the graveyard is specifically opposed to the royal court, and not just because of the dirt and bones and all. In Act I the court is a place where Hamlet's told to "not for ever with they vailèd lids/ Seek for thy noble father in the dust" (1.2.72-73) and reminded that "your father lost a father,/ That father lost, lost his" (1.2.93-94): in other words, there's no time to remember the dead. People die; get over it; move on.

But not in the graveyard. In the graveyard, Hamlet's allowed to remember the dead. "Alas, poor Yorick," says Hamlet, as he recalls that Yorick was "a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy," one who "hath borne [Hamlet] on his back a thousand times" (5.1.190-191; 191-192; 192-193).

So, Hamlet encounters the skull of a man who worked for his father and who Hamlet knew as a child. He remembers his childhood as a happy time in which Old Hamlet was alive and all was well in the world. All this happiness, of course, is disrupted when Hamlet realizes Ophelia (now dead) is being buried a few gravestones over.

We'll let you handle that one on your own.