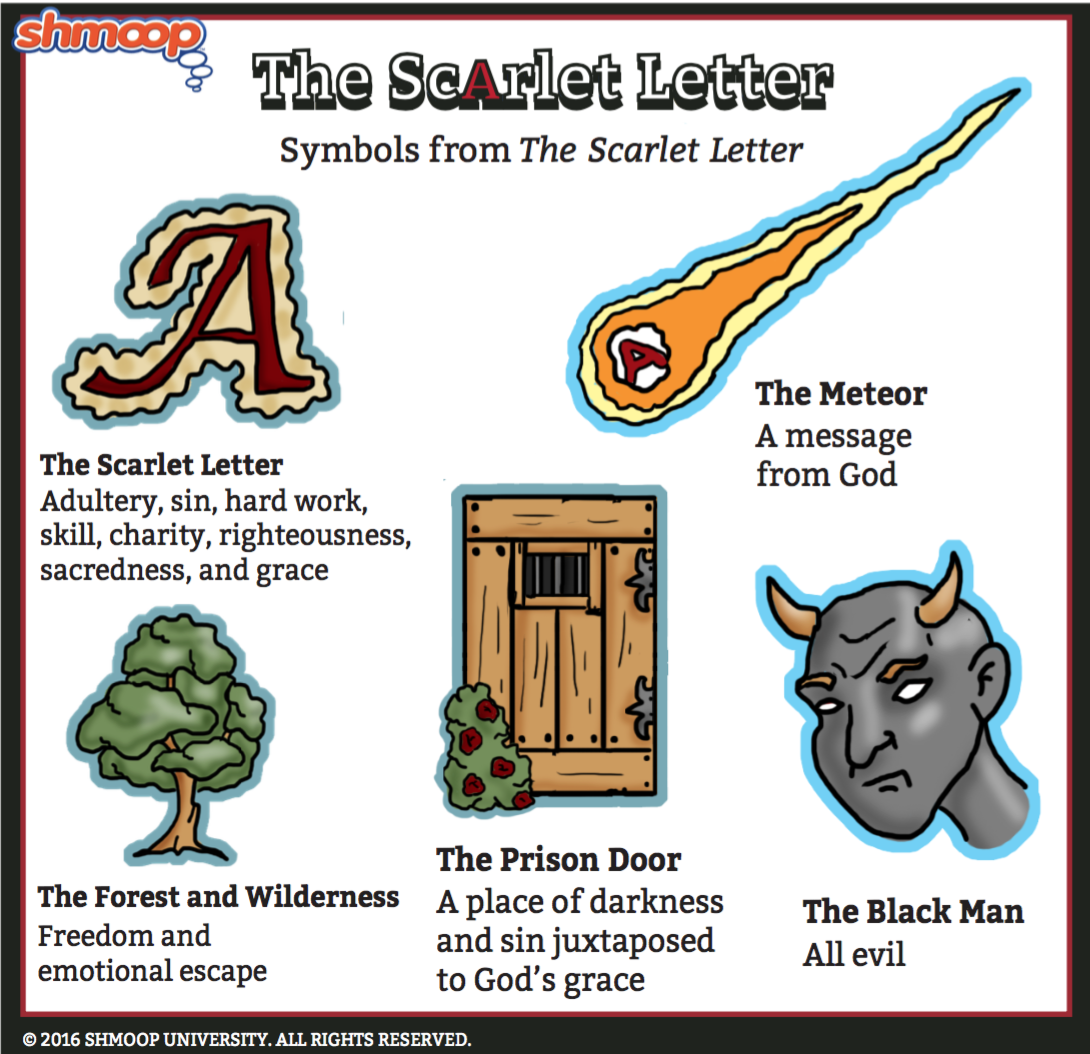

Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory

(Click the symbolism infographic to download.)

To the townspeople, the forest is the unknown. It's outside of the town, it's full of American Indians and scary creatures, and, worst of all, it's utterly lawless. The town is ruled by law and religion; the forest a place of passion and emotion.

We see this when the narrator compares Hester's outcast state to a forest: "She had wandered, without rule or guidance, in a moral wilderness; as vast, as intricate and shadowy, as the untamed forest" (18.2). In other words, Hester is cast out of the rules and order of the town, forced to live in a metaphorical forest: a wilderness of shadowy right and wrong.

Obviously, Hester's little cottage is "on the outskirts of the town… out of the sphere of that social activity which already marked the habits of the emigrants" (5.4).

Into the Woods

But while the Puritans seem to be kind of terrified of the forest, the narrator isn't. In fact, the narrator associates Nature with kindness and love from the very beginning of this story, when the wild rosebush reminds all that "the deep heart of Nature could pity and be kind to him" (1.2).

It's not that the woods are all sweetness and light. They can be dangerous, too. After a few hours in the woods with Hester, Dimmesdale becomes so mischievous that he can hardly keep himself from whispering an "unanswerable argument against the immortality of the human soul" (20.7). (Shock!) But we get the feeling that the narrator kind of wants to see it happen.

Or take the brook that Pearl plays with:

All these giant trees and boulders of granite seemed intent on making a mystery of the course of this small brook; fearing, perhaps, that, with its never-ceasing loquacity, it should whisper tales out of the heart of the old forest whence it flowed, or mirror its revelations on the smooth surface of the pool. Continually, indeed, as it stole onward the streamlet kept up a babble, kind, quiet, soothing, but melancholy, like the voice of a young child that was spending its infancy without playfulness, and knew not how to be merry among sad acquaintances and events of somber hue. (16.23)

It may be childlike, but it's a sad child, a child who doesn't know how to play. (Gee, like Pearl?) Here, the forest seems to represent potential: that part of human nature that can't be squashed and beaten into submission. It's a place where the soul can be free, with all its wild passions and crazy ideas and secret sorrows; it's a place for Hester and Dimmesdale to meet in "solitude, and love, and anguish" (22.6), where they "deeply" can know each other.

If life on the town is all surface and appearance and rules, then life in the forest is all depth and emotion. And you can't live like that—you can't live in the woods. But you sure can visit every once in a while.