Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

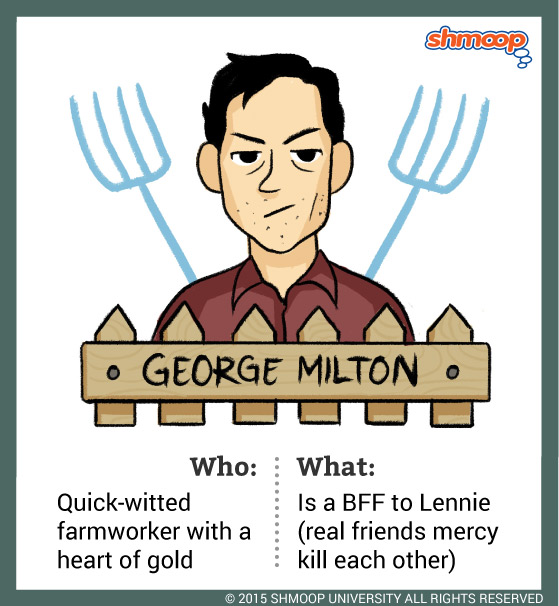

George Milton is our hero, a roving farmworker who is "small and quick, dark of face, with restless eyes and sharp, strong features … [with] small, strong hands, slender arms, and thin and bony nose" (1.4). But there's more to him than a smart mouth and quick brain: he may not show it much, but George is a deeply moral, good man.

Let's find out what makes him tick.

With Friends Like This, Who Needs Enemies?

Oddly, what makes George tick is his big, dumb oaf of a friend, Lennie. But George isn't about to give Lennie one of those BFF heart necklaces you bought in Claire's in sixth grade. (Although Lennie might buy George one.) In fact, he's not very nice to Lennie at all. Take George's very first words:

"Lennie!" he said sharply. "Lennie, for God' sakes don't drink so much." (1.6)

Tender loving care? Not exactly. And check out his the way he yells at his so-called friend when they talk about ketchup:

"Well, we ain't got any … God a'mighty, if I was alone I could live so easy. I could go get a job an' work, an' no trouble. No mess at all, and when the end of the month come I could take my fifty bucks and go into town and get whatever I want. Why, I could stay in a cathouse all night. I could eat any place I want, hotel or any place, and order any damn thing I could think of. An' I could do all that every damn month. Get a gallon of whisky, or set in a pool room and play cards or shoot pool… An' whatta I got … I got you! You can't keep a job and you lose me ever' job I get. Jus' keep me shovin' all over the country all the time." (1.89)

When you put it like that, it doesn't make much sense at all that George would stick with Lennie. But he has his reasons: he doesn't actually want to be staying in cathouses and pool rooms and hotels and the bottom of whisky bottles. Most ranch hands, George says, are lonely, bitter men—but not Lennie, and not him: "We got a future. We got somebody to talk to that gives a damn about us. We don't have to sit in no bar room blowin' in our jack jus' because we got no place else to go. If them other guys gets in jail they can rot for all anybody gives a damn. But not us" (1.115).

Lennie may not be much company, but he's company. He gives George someone to care about and someone to think about. Even Lennie's dangerous water-drinking habits let George show that he cares, even when he's saying "The hell with the rabbits. That's all you can ever remember is them rabbits" (1.18-19). George may get tired of the rabbits, but he still tells Lennie's favorite bedtime story about their dream farm, and he still looks after Lennie as much as he can.

The World Will Dream as One

Lennie definitely benefits from their friendship, but he's not the only one. George gets companionship, and he also gets a chance to dream. At the end of the novel, after Lennie is dead, George tells Slim about the farm, saying, "—I think I knowed from the very first. I think I knowed we'd never do her. He usta like to hear about it so much I got to thinking maybe we would" (5.78).

On his own, George knows that the farm is just a silly dream, like imagining that you're going to live in a Malibu mansion someday. (Unless you already live in a Malibu mansion, in which case, go you! Live the dream!) But with Lennie, George can believe. You know the children are our future? Lennie is like George's child. With Lennie around, he can believe that there's actually a future, a real American Dream waiting for them just around the corner.

Cathouses and Poolrooms

All this hope makes George's ending even more tragic than Lennie's. Sure, Lennie dies—but it's a merciful death, and, in the context of the story, he's probably better off. (At least, Steinbeck seems to think so.) But George has become one of the lonely ranchhands that he describes at the beginning of the novel, those men who "got no fambly. They don't belong no place. They come to a ranch an' work up a stake and then they go inta town and blow their stake, and the first thing you know they're poundin' their tail on some other ranch. They ain't got nothing to look ahead to" (1.113).

But George and Lennie have each other—until they don't. After Lennie dies, George tells Slim, "I'll work my month an' I'll take my fifty bucks an' I'll stay all night in some lousy cat house. Or I'll set in some poolroom til ever'body goes home. An' then I'll come back an' work another month an' I'll have fifty bucks more" (5.79-80).

Now, George is just like everyone else. He's a lost soul of the Great Depression, a homeless man traveling from farm to farm in search of menial, contingent work. He has nothing to live for, and no expectation that things will ever improve. Lennie may have been big, dumb, and annoying, but he also made George special.

A Man's Work

We could also say that George still is special: he has the innate moral clarity that lets him see that killing Lennie is the right thing to do.

Let's contextualize this, Shmoopers: when George kills Lennie, it's a kind of euthanasia, or mercy killing. Euthanasia is a hotly debated political and moral question, and Shmoop likes to remain studiously neutral on these topics. However, in the contest of this novel, it seems pretty clear that killing Lennie is the right thing to do, and that George is manning up by pulling the trigger.

How do we know this? First, we have the contrasting example of Candy, who says that he "shouldn't ought to of let no stranger shoot [his] dog" (3.234). Second, Slim says, "You had, George. I swear you hadda" (5), and Slim is the novel's ideal man (check out his "Character Analysis" for more on that).

So, does George tell us that masculinity means being able to kill things for their own good? Or is this simply our only option, in a messed-up, hopeless world?

Solving Quadratic Equations by Factoring