Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

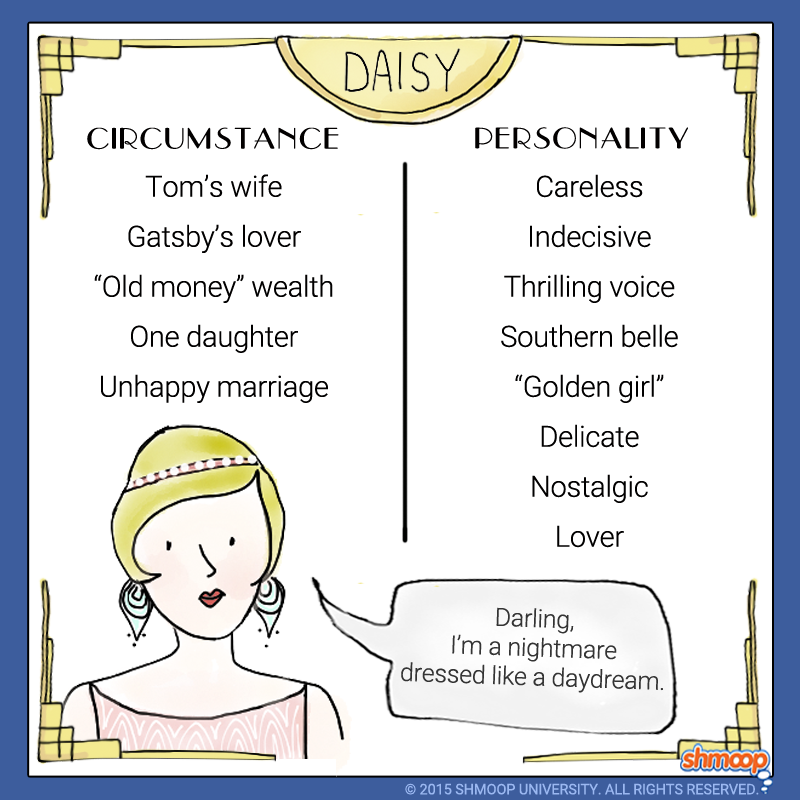

In The Great Gatsby, Gatsby's entire life is devoted to the faint hope of rekindling his old love affair with Daisy. But what's so great about this Daisy, anyway?

Siren Song

Well, to start, she's got a

I looked back at my cousin, who began to ask me questions in her low, thrilling voice. It was the kind of voice that the ear follows up and down, as if each speech is an arrangement of notes that will never be played again. Her face was sad and lovely with bright things in it, bright eyes and a bright passionate mouth, but there was an excitement in her voice that men who had cared for her found difficult to forget: a singing compulsion, a whispered "Listen," a promise that she had done gay, exciting things just a while since and that there were gay, exciting things hovering in the next hour. (1.33)

There's a "singing compulsion," an "arrangement of notes" that makes men wild. It's full of promises, hints that wonderful things are on the horizon.

Thinking about Gatsby stretching his arms out to the green light across the water, we can't help thinking of the Sirens: the mythical island dwellers whose singing was so seductive that sailors would throw themselves into the sea and drown trying to reach them. To Gatsby, Daisy's seductive voice speaks of wealth, social status, glamour, family, and of course Daisy herself—everything that Gatsby wants.

Lover

Daisy's voice makes her sound untouchable. Nick thinks of it as "full of money," and that it sounds like it belongs to someone who lives "high in a white palace, the king's daughter, the golden girl […]" (7.99). You know, the prom queen, the sorority president, the pageant winner: exactly the kind of girl that neither Gatsby nor Nick would ever have a chance with.

But Tom does. And Daisy may marry him at first because she feels like she has to, but she does end up falling in love with him. (Or at least lust.) Jordan clues us in:

If he left the room for a minute she'd look around uneasily, and say: "Where's Tom gone?" and wear the most abstracted expression until she saw him coming in the door. She used to sit on the sand with his head in her lap by the hour, rubbing her fingers over his eyes and looking at him with unfathomable delight. (4.143)

This doesn't sound to us like a girl living "high in a white palace." It sounds like a pretty normal 20ish year old, head-over-heels in love with her husband. What we learn from this is that Daisy isn't just a frivolous rich girl—or, she wasn't always. She has a deep capacity for love, and she wants be loved.

And if that's what she wanted, it's pretty clear that she married the wrong guy.

Poor Little Rich Girl

Or maybe she didn't marry the wrong guy; maybe she just likes to think that she did. One of the things Gatsby and Daisy share is an idealized image of their relationship, a rose-colored view makes everything in the present seem dull and flat in comparison. She longs for the innocent period of her "white girlhood," before she was forced/forced herself into her marriage to Tom. Though the Daisy of the present has come to realize that more often than not, dreams don't come true, she still clings to the hope that they sometimes can.

And to Daisy, most of this trouble comes down to one fact: she's a girl. In her mind, women (or girls—Fitzgerald never uses "women" when he could use "girls") need to be foolish. They need to be as careless as Nick ends up thinking that she is, because the world is cruel to women. When her child is born, she tells Nick, she weeps: "'All right,' I said, 'I'm glad it's a girl. And I hope she'll be a fool – that's the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool'" (1.118).

If Daisy had been a fool, she would have accepted her fate. She would have married Tom—her right, as the beautiful Southern belle that she was; she would have had kids and ignored them; and she would have turned a blind eye to Tom's philandering with the housemaids. But she didn't.

Daisy the Child

Daisy may be a married woman with a child, but she doesn't seem like she's managed to grow up very much. She can't live with the consequences of her actions, trying to (drunkenly) change her mind on the night before her wedding (4.120), and then being unable to make up her mind between Tom and Gatsby: "I did love him once," she says, "but I loved you too" (7.266).

Pure-hearted Gatsby can't understand this kind of indecision. But to Daisy, it's just part of the girlhood: she's never learned how to be a woman, and we get the feeling from this novel that she's never going to. There's no one to teach her. She's expected to be a "beautiful little fool," just like every other girl of her social class.

And ultimately, like a kid, she lets Tom make the decisions for her. She's used to her life being a certain way – she follows certain rules, she expects certain rewards – and when Gatsby challenges her to break free of these restraints, she can't deal. Ultimately, Daisy returns to Tom because facing a life without a $300,000 pearl necklace is even worse, apparently, than facing life with her "hulking" brute of a husband.

Do we blame her? Is she responsible for her poor choices? Or is she just living her life in the best way she knows how to live it?

Daisy's Timeline